Salmon are one of the most well-known species found in the Fraser Watershed. They are anadromous fish, meaning they spend parts of their life in both freshwater and saltwater habitats. Salmon begin life in freshwater rivers, streams and lakes but live their adult lives in the ocean before returning upriver to reproduce. The Fraser River is home to five species of Pacific salmon: Chinook, Coho, Chum, Sockeye, and Pink. Salmon are keystone species, and both aquatic and terrestrial habitats in the Pacific Northwest depend on stable salmon populations to thrive.

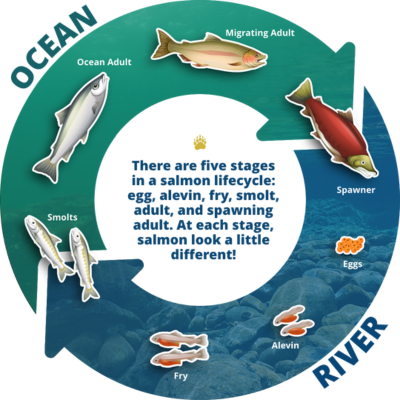

Let’s dive a bit deeper into the fascinating lifecycle of salmon!

Egg

On average, female salmon lay between 2,500-5,000 eggs while spawning, deposited in nests called redds which she digs in the gravel with her tail to create. Salmon eggs are translucent and are vibrant shades of red or orange. You may assume this colouring is why the nests are called redds, but the term has Scottish roots and means “to clean an area or make it tidy.” Inside the protection of the redd, the eggs are safe from predators and exposure as they develop. Incubation time for salmon eggs is dependent on environmental factors, but they usually hatch 2-3 months after being laid.

Alevin

Upon hatching, young salmon are considered alevin. They remain in the safety of the redd for several weeks while they continue to develop and grow, with nutrients from their yolk sac providing sustenance. Once the yolk is fully absorbed, the alevin will begin to swim and will journey away from the redd.

Fry/Parr

Salmon fry emerge from the redd to find calm waters where they feed on small insects, crustaceans and other prey. At this life stage, juvenile salmon develop parr marks, which are dark ovals or bands on the sides of young salmonid fishes. Salmon with these markings are often called parr or fingerlings. Each species has distinct marking patterns that help salmon camouflage to hide from predators. Some species, such as coho and sockeye salmon, spend long periods in freshwater while others, such as pink salmon, immediately swim for the ocean.

Smolt

As the juvenile salmon grow, they journey closer to the ocean and adapt to salt water in brackish estuaries. During this life stage salmon are called smolts and they begin their physiological changes to adapt to the ocean. This process is called “smoltification”. The parr colouration fades away and is replaced by the silvery shine of an adult salmon. There are no rigid rules or timelines for smoltification across species and populations.

Adult

It is estimated that less than four smolts from each redd will become adults. Little is known about salmon’s lives in the ocean outside of what is observed in coastal waters. These silvery adult fish will often swim thousands of kilometres each year in schools. Salmon spend 1-7 years in the ocean, depending on the species and population. They feed mainly on zooplankton but also prey on squid and smaller fish. Chum salmon will even eat jellyfish. While in the ocean, salmon are preyed upon by seals, sea lions, sharks, orcas, and humans.

Spawners

In the late summer through fall, salmon will migrate back to their natal rivers and tributaries. Salmon will wait at the mouths of rivers as they acclimate to freshwater and wait for rains to raise water levels that make their journey easier. Some salmon will travel as far as 3,000 km (2000 miles) to reach their spawning grounds. At this stage, most salmon stop eating and work off of their energy reserves. They transform from silvery ocean bodies to olive, red, and green shades with humped backs, hooked jaws, and canine-like teeth. Upon reaching their spawning grounds, female salmon construct redds that they defend, while males compete with one another for mating privileges.

Death

Salmon are semelparous, which means they only have a single reproductive cycle before death. Many salmon will die within a few days after spawning, but some salmon may survive for weeks as their bodies begin to deteriorate and rot. These nearly dead salmon are commonly nicknamed “zombie salmon.” In their death, salmon move billions of tonnes of nutrients from the ocean to the terrestrial and freshwater habitats. It is estimated that at least 137 species rely on this process. Studies have shown that decaying salmon contribute 25% of nitrogen in riparian zone vegetation along salmon rivers.

Speaking of Salmon…

Protecting and restoring fish habitat in tributaries throughout the Fraser Watershed is critical to the survival of this magnificent migratory species. If you’re interested in habitat restoration, visit the Foodlands Corridor Restoration Program page to learn about ongoing restoration efforts happening on the sc̓e:ɬxʷəy̓əm (Salmon River).

A watershed-wide effort is needed to achieve protection and restoration goals. We can’t do it alone. Please give today to support a resilient Fraser Watershed.

Together, we can secure a healthy, resilient watershed that safeguards the habitat of migratory fish and protects their vital role in our ecosystem.